Canada, U.K. and European Union back off electric-vehicle targets as economic reality sets in and even China shows cracks

The U.S. retreat from its electric-vehicle ambitions is spreading around the globe.

In Canada, Prime Minister Mark Carney paused an electric-vehicle sales mandate that was set to take effect next year. In the U.K., Prime Minister Keir Starmer has allowed for a more flexible timetable to hit the country’s EV targets. And the European Union last month bowed to pressure from automakers to rethink—a year earlier than planned—its 2035 target for eliminating carbon-dioxide emissions from cars.

“There’s this realization that, ‘Hey, this transformation isn’t going as fast as we want,’” said Patrick Schaufuss, a partner at consulting firm McKinsey. “EVs aren’t smartphones.”

Automakers have been saying that consumers aren’t adopting EVs as quickly as expected, and government efforts to proliferate the technology are hammering their bottom lines. GM, in announcing its charge, said it is reassessing EV capacity and warned that more losses are possible.

The reality is hitting hard in the U.S. General Motors said Tuesday that it would take a $1.6 billion charge because of sinking EV sales, a shift it blamed on recent moves by the U.S. government to end EV subsidies and regulatory mandates. The automaker has lobbied heavily this year to loosen EV requirements.

That might just be the beginning of a financial reckoning from automakers that poured billions into new electric models—from sports cars and sedans to big pickups and sport-utility vehicles—to try to get ready for the government-backed EV mandates.

“There is more realism that EVs are probably a good solution in the future, but it’s not going to be forced down the throat of customers,” said Christian Meunier, chairman of Nissan Americas, referring not just to the U.S. but to much of the Western world. “It’s pragmatism.”

Carmakers argue the EV business model is an unprofitable proposition given still-high battery costs, spotty car-charging networks and dwindling government subsidies. Incentive programs have ended or have been pared back across Europe and in the U.S. and Canada.

Volkswagen, burdened with massive electrification costs, helped spur the reckoning in Europe when it said it would cut 35,000 jobs as part of a deal with its union. The move sent shock waves through the region’s political establishment.

Weeks later, the EU launched a “strategic dialogue” with the automotive industry that led to a more flexible timetable for automakers to meet its emissions rules for 2025.

After another round of talks last month, EU industry commissioner Stéphane Séjourné said a 2035 target for cutting carbon emissions from cars to zero would be reviewed as soon as possible, according to a spokesperson.

The lobbying effort from European automakers to water down EV mandates was in high gear at last month’s Munich auto show, where they jostled with Chinese newcomers such as BYD, XPeng and GAC to launch eye-catching electric models.

Jean-Philippe Imparato, then European boss of Stellantis, which owns brands including Fiat, Peugeot and Jeep, said in an interview at the Munich show that he considers the EU’s targets for 2030 and 2035 unreachable.

Volkswagen Chief Executive Oliver Blume, speaking to reporters, called for better charging infrastructure, cheaper electricity and subsidies for entry-level vehicles. “We are still not there,” he said. “You can’t punish the automotive industry for something they couldn’t influence 100%.”

The shifting landscape—and the challenge it presents to automakers—was in focus as Blume, who also is CEO of Porsche, showed off coming vehicles.

He touted a family of small EVs designed to compete with new Chinese rivals in the company’s home market. He also showed off the latest version of Porsche’s 911 Turbo S sports car, in a sign of the industry’s renewed interest in internal-combustion engines, particularly at the luxury end of the market.

A policy note published before the recent EU talks enumerated the European car industry’s continuing challenges, including higher tariffs on shipments to the U.S., low EV margins and the rise of Chinese brands with a cost advantage.

“We need to listen to the voices of the stakeholders that ask for more pragmatism in these difficult times,” European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said earlier this year.

Before he was Canada’s prime minister, Carney spent a decade advocating for the fight against climate change. By the time he took office this spring, Canada had a more immediate crisis: President Trump had levied debilitating tariffs on some of the country’s biggest industries, including 25% duties on cars, steel and aluminum.

Months of rising unemployment and gross-domestic-product declines followed. Carney shifted from green-centric to laser-focused on bolstering Canada’s economy. Last month, he paused an EV-sales mandate set to take effect next year, a move aimed at easing an auto industry bruised by Trump’s trade wars.

“We’re at the start of a restructuring in the Canadian auto sector,” Carney said as he announced the decision. “And the suspension of the EV mandate for 2026 is part of helping with that.”

Carney said officials would review the existing EV policy and look for ways to reduce costs and to potentially bring more affordable EVs to Canada.

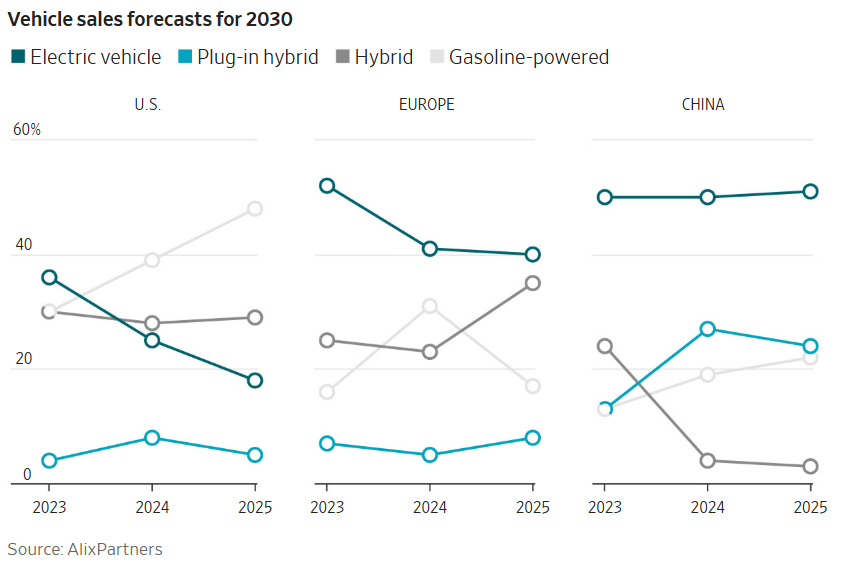

Even China, the world’s most dominant EV market, is showing cracks. Sales continue to grow, but increasingly at the expense of profitability as carmakers fight for customers in an oversaturated market. Consulting firm AlixPartners predicts that most of the 118 EV brands operating there in 2023 won’t be viable five years from now.

Where China has doubled down on EVs, Japan has largely avoided the tumult by pushing for vehicles that pollute less without requiring specific technologies. The country includes hybrids in government targets.

In the EV boom’s early days, Japan’s Toyota Motor took heat for largely skipping EVs in favor of hybrids. Chairman Akio Toyoda at the time described himself as part of a silent majority in questioning the wisdom of the global EV push. Toyota instead focused on gas-electric hybrid vehicles, a technology it pioneered with the Prius.

The reality check abroad is less dramatic than in the U.S., where EV sales have disappointed in recent years and are now expected to plunge after Congress and the Trump administration largely did away with federal support, from tax credits for buyers to regulations requiring cleaner, more fuel-efficient vehicles.

GM, which until recently aimed to have an all-electric lineup by 2035, and the U.S. industry’s main trade group successfully lobbied this year to take away California’s ability to set its own tailpipe-emissions standards. The victory effectively killed the country’s biggest driver of EV investment.

The U.S. also did away with fines for automakers that fail to meet federal fuel-economy standards and a $7,500 tax credit for electric-car buyers.

In the U.S., AlixPartners now predicts EVs will make up 18% of new-vehicle sales by 2030, half of what it expected two years ago.

Write to Sharon Terlep at sharon.terlep@wsj.com and Stephen Wilmot at stephen.wilmot@wsj.com