Attacks from short sellers and the collapse of auto lender Tricolor haven’t slowed down America’s most valuable used-car retailer

A white 2024 Tesla Model Y slowly rolls down the lane through a crowd of mostly men dressed in golf shirts and jeans. The onlookers, buyers from car dealerships who’ve all descended onto this auction site in Chandler, Arizona, snap photos of the vehicle and place bids by raising their hand or using their phone. A screen hanging nearby lists the current bid at $30,000. The Tesla sits there for barely two minutes before the sale is closed and the driver, wearing a bright orange vest, moves it along. Next up: a tired-looking green 2006 Isuzu Ascender. A burly auctioneer with a dark goatee rhythmically chants, “Homina, homina, homina, opening bid, $1,100.” The screen says grimly that the car is being sold “as is.”

The site, one of 56 across the US, is owned by Carvana Co. It’s not something you’ll hear about in the many commercials Carvana runs on TV and podcasts about the happy experience of buying and selling a used car online, and there’s no gimmicky car-vending-machine tower in sight. The Chandler location sells 1,000 cars a week—some come in after drivers’ leases expire; some are traded in by dealerships; some are rentals retired from Hertz and Enterprise. Carvana offloads the models it doesn’t want to competitors and keeps others to list for sale on its site.

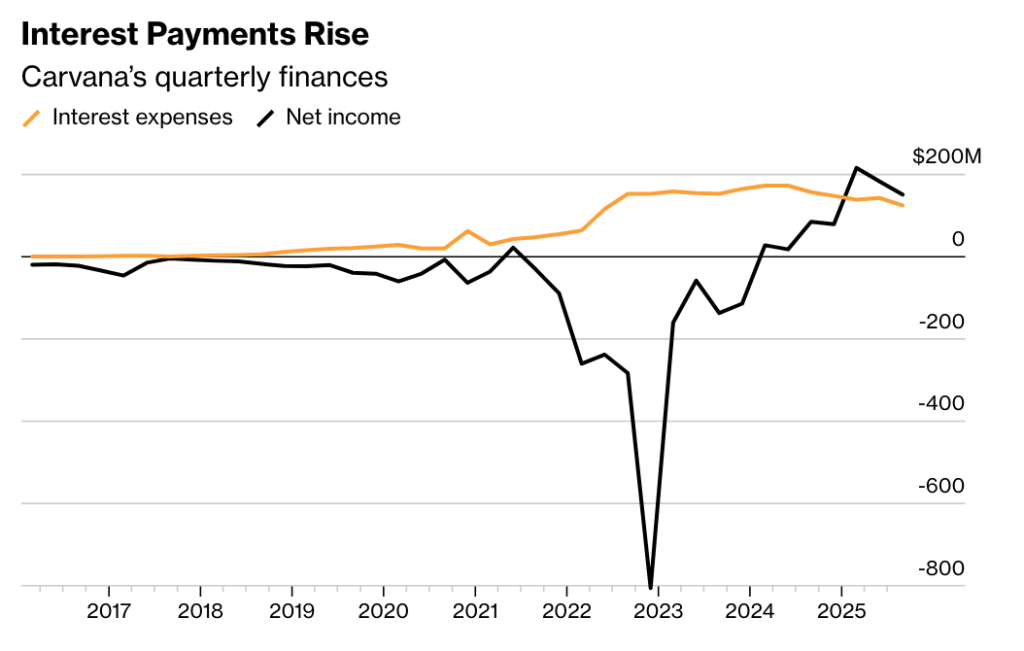

Carvana is by far the most valuable used-car seller in the US, and it wants to become the Amazon.com of cars. To try to accomplish this Ernie Garcia III, the co-founder, chief executive officer and chairman, did the most American of things: He loaded the company up on debt. It took out $3.5 billion in high-interest loans to buy an auction house named Adesa just as the Covid-19-fueled fever dream in sky-high used-car prices was winding down. The timing was disastrous. Short sellers circled, sensing an opportunity to profit from a falling share price, and Carvana—a pandemic meme stock—suddenly lost 99 percent of its market value. But investors got over it. The shares reached an all-time high in January, and debt remains a big part of the story. Many of Carvana’s customers—like the company, whose bonds are rated junk—have less-than-stellar credit histories but want to take out a loan, which they do through Carvana. The entire business runs on a cycle of borrowed money.

For now, the market is supporting Carvana’s ambitions. Prices for new cars are near record highs, after automakers restricted production to boost profits, which is creating plenty of demand to buy used. Even with an uptick in subprime borrower delinquencies industrywide and the collapse of auto lender Tricolor Holdings LLC, Carvana keeps cranking out loans using its own in-house approval system, and those loans are plenty profitable. (That’s despite the company’s subprime borrowers having even lower credit scores than those of Tricolor, according to research from JPMorgan Chase & Co. On average, though, Carvana’s customers have higher scores because it originates prime loans too.)

There’s still plenty at risk. Carvana’s stock is perpetually vulnerable to aggressive short sellers. On Jan. 28 Gotham City Research LLC published a report accusing Carvana of inflating its valuation by overstating earnings and obscuring transactions between different Garcia family-owned businesses, sending shares plummeting 14 percent that day. Although Carvana dismissed the report’s claims and the stock price has begun to recover, the company’s otherwise lofty valuation is driven by an expectation that its rapid sales growth will continue. If it doesn’t, Carvana will be carrying substantial expenses from its rampant expansions. But for the moment, selling auto loans is a good business if you can get it. Carvana, which makes most of its income by selling the loans it originates, has been steadily turning a profit for almost two years. It originated $9 billion in loans in the first nine months of 2025 and has had no trouble finding buyers for the debt. The biggest, Ally Financial Inc., pledged in October to purchase $6 billion worth over the next year, and Carvana says it has agreements with two other companies it declined to identify that will each buy $4 billion more this year.

That’s helping finance the next stop for that white Tesla and other vehicles that will end up on Carvana.com. Across the parking lot from the auction site is a cavernous garage where a hive of workers inspect, repair and buff up hundreds of cars a day. The company added the facility in April, making it one of 16 Carvana megasites that host auctions and recondition cars. The operation brings in more inventory for the website and secures valuable real estate near major cities where Carvana can receive cars, fix them and ship them to customers. That in turn reduces the number of long-distance deliveries the company has to make.

Garcia III is doing what he’s always done when things are going well: He’s pushing for more growth. Late last year Carvana began selling new cars for the first time. It’s doing so in the most low-tech way. The company has bought five dealerships in recent months, selling new vehicles exclusively from the Euro-American auto conglomerate Stellantis NV. The dealerships—in the Atlanta, Dallas, Phoenix, Sacramento and San Diego areas—look like any other and sound as if they were named by a bad search engine optimization consultant: Carvana Chrysler Dodge Jeep Ram.

If one of the locations doesn’t have the color or configuration a shopper is looking for on the lot, it can order from one of the others and have it shipped by truck. Other dealers do this, but few have the potential scale that Carvana can bring. Stellantis declined to comment, and Carvana wouldn’t say much about this new business, other than to call it an experiment. In fact, the idea has been on Garcia’s mind since at least 2017, when he met with executives from France’s Groupe PSA—now owned by Stellantis—about reviving the Peugeot brand in the US, say people familiar with the discussions who asked not to be identified because the meetings were private. (Sadly, Peugeot isn’t coming back anytime soon.)

There are many reasons why the new-car business is appealing to Garcia. It introduces the brand to a more affluent consumer and makes the business less dependent on borrowers with lower and riskier credit profiles. It’s also a good way to bring in more decent used cars because—despite all of Carvana’s advertising about the benefits of selling your vehicle online—many people prefer to trade in their old cars at dealerships when they buy new ones. Plus, new cars need maintenance too.

Carvana’s infrastructure can easily support the dealerships. The company’s reconditioning centers could support twice as many cars as they’re taking in today. According to the company, Carvana could refurbish as many as 1.5 million vehicles a year, well beyond the 600,000 or so it sold in 2025. If the company keeps finding customers and sustains its growth—a 45 percent increase in used-car sales last year—it could be a profit machine. If it doesn’t, it’ll have a bunch of giant, underused auto-repair shops.

“We’ve just got to grow into it,” Garcia tells Bloomberg Businessweek. “It’s just about growing the whole machine as we go.”

Although it’s not written into the company’s official history, Carvana is a father-son story. It dates to 1991, when Ernie Garcia II, the CEO’s father and a former real estate developer in Arizona, bought the assets of a bankrupt rental-car company called Ugly Duckling Corp. The business, founded in the 1970s by an insurance salesman named Thomas Duck, failed to keep up with Hertz Global Holdings Inc. and Enterprise Holdings Inc., and filed for bankruptcy. Garcia II, who’d just pleaded guilty to bank fraud related to the Lincoln Savings & Loan scandal, spent less than $1 million on the deal and soon shifted the company away from rentals and toward used cars and high-interest loans.

The elder Garcia took the company public in 1996 under the ticker UGLY and expanded to about 80 locations. The stock did well, until a succession of bankruptcies in the subprime auto-loan industry and the 2001 stock crash caused investors to flee. Garcia II made two attempts to take Ugly Duckling private. He finally succeeded in 2002, renaming the company DriveTime Automotive Group Inc. It specializes in so-called buy here, pay here, where consumers with bad credit could get the keys to a vehicle financed directly through DriveTime instead of applying to a third-party lender.

The company developed a reputation for selling old cars with a lot of miles and dispatching aggressive debt collectors. In 2014 the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau accused DriveTime of making harassing collection calls to customers and providing false information to credit reporting agencies. DriveTime settled the case for $8 million without admitting wrongdoing and said it was taking steps to improve customer service and compliance.

At age 24, Garcia III was given the job of treasurer at his dad’s company, but he had bigger goals. In 2011 he pitched a venture to sell used cars on the internet. His father thought it was a dumb idea. People want to test-drive a car and look under the hood before buying it, Garcia II said. What if they could offer a seven-day return guarantee? Garcia II said the cost of shipping cars back and forth when they’re returned would kill the business. “I didn’t think anyone would buy a car online,” he says. “If anyone but my son asked me to invest in this idea, I’d have politely told them to leave my office.”

Instead, he handed his son $5 million and a small team from DriveTime to get started. Carvana sold its first cars to customers in Atlanta in 2013. Teresa Aragon, who was in that first batch of employees from DriveTime and is now Carvana’s vice president for customer experience, recalls working 13-hour days, seven days a week and taking customer-service calls while driving her kids to school.

Garcia II went on to invest $150 million more in his son’s company, giving him the largest position today. Father and son control more than 80 percent of the special Class B shares, which have 10 times the votes of a normal Carvana share. And three of the board’s six members used to work for DriveTime. Despite being publicly traded, the company behaves like a founder-controlled startup.

The relationship between Carvana and DriveTime runs deep. For a while Carvana used DriveTime’s reconditioning centers to prep cars for sale and rented space in DriveTime’s offices. “Building up that infrastructure would have taken years and cost a fortune,” says the elder Garcia, who’s the executive chairman at DriveTime and doesn’t have an official role at Carvana. Even now, Carvana relies on DriveTime to provide vehicle service contracts, which customers can buy to help cover the cost of future repairs, and to process loan payments from customers. Carvana booked $193 million in commissions on those DriveTime warranties last year alone, according to a corporate filing.

DriveTime eventually got its own website, where it lists its inventory and allows people to apply for loans. The two companies are differentiated, in part, by the credit scores of their customers. DriveTime’s tend to have lower credit scores than Carvana’s, which attracts a wide range of customers across income bands and carries fresher cars. The average car sold on Carvana is three and a half years old.

Early on, Carvana had limited presence in big US coastal cities because its repair shops were mainly in the Midwest and South. The real estate was cheaper and easier to find in those regions, enabling the company to build reconditioning centers and car vending machines, an early marketing ploy that’s basically a tall parking garage where customers can drop off their old car and pick up a replacement they ordered online. Opening a new site could take 20 months or more, says Brian Boyd, the company’s senior vice president for inventory. For one location, in Rocklin, California, it took three years to secure the necessary approvals, and when contractors were ready to start paving, local officials discovered an owl nesting in the area. That delayed the project for many more months, until the owl decided to leave. The CEO and his team began to see these build-outs—and the land purchases, zoning board meetings and construction contracting they require—as impediments to growth.

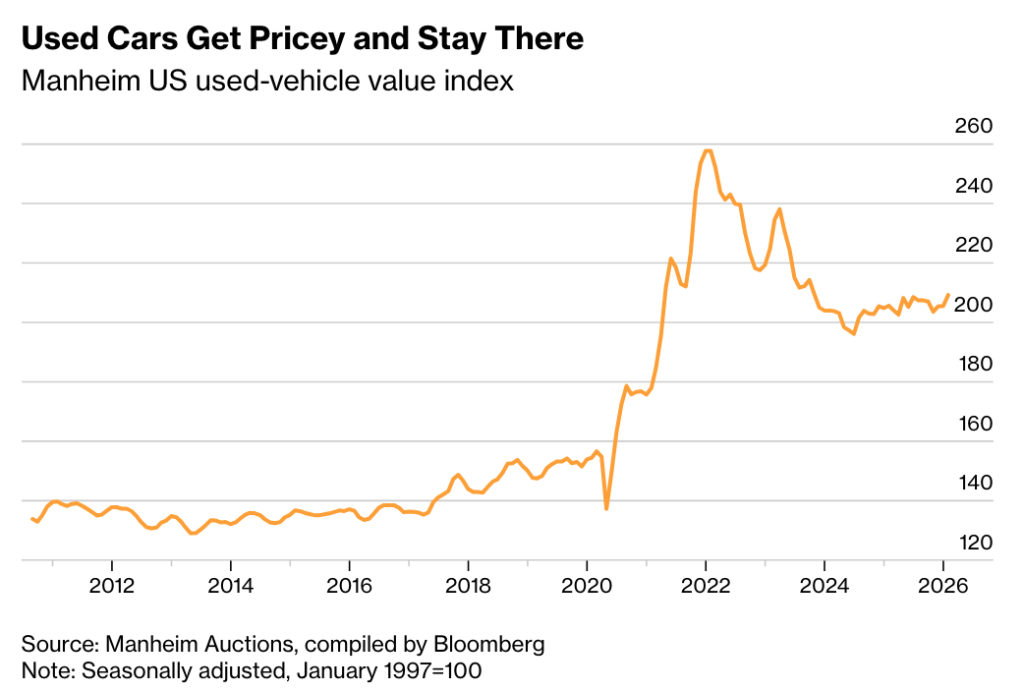

Boyd floated the idea of an acquisition to fast-track expansion, which led them to the auction company Adesa. “The mandate from the market was: Grow revenue,” Boyd says. Carvana announced the deal in February 2022, the same month used-vehicle prices reached an all-time high. It was only downhill from there. The company had to sell some cars at a loss, and those it didn’t sell were quickly depreciating in value. The Federal Reserve raised its benchmark interest rates throughout that year, only introducing more volatility into the business.

As the stock nosedived, it came to light that father and son had made some very fortuitously timed stock sales. Investors sued, alleging a pump-and-dump scheme. The Garcias have said the suit is without merit, and the case is ongoing.

Jim Chanos, who became famous for shorting Enron before its collapse, is among those betting against Carvana. In addition to concerns about all the Garcia family dealings, Chanos argues that the company’s biggest profitmaker—selling loans it made to people with shaky credit records—depends on a healthy economy. If more people stop paying their bills, Carvana could have trouble selling its loans. And while declining interest rates could encourage more people to finance their purchases, economic trouble often means high delinquency rates. Chanos says it wouldn’t take a full-blown recession, only a bit of economic uncertainty, to disrupt Carvana’s chief income source.

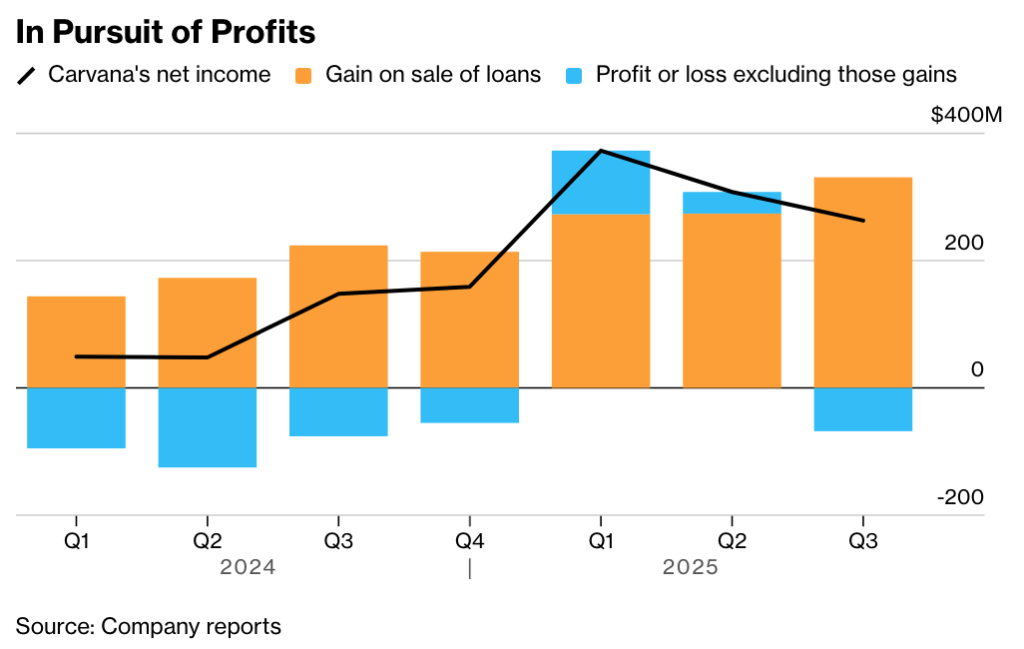

Chanos faults Carvana for the way it reports profits, a critique echoed by the Gotham City Research report that sent the stock plunging in January before some analysts came to the company’s defense. The company’s financial disclosures tend to emphasize numbers that exclude substantial fixed costs, such as depreciation costs on its auction houses, dealerships, reconditioning centers and interest payments on corporate debt, he says. “The stock is in the momentum bucket with others like Robinhood that are popular with retail traders,” Chanos says. “The quality of earnings is not great at all.”

Of course, not every short sale pans out for Chanos. He described his bet against Tesla as “painful”. Hindenburg Research, another prominent short seller, staged its own campaign in January 2025 with a report titled Carvana: A Father-Son Accounting Grift for the Ages. But the stock kept climbing, and Hindenburg closed its doors.

The controversy over the insider stock transactions didn’t stop the Garcias from selling. Garcia II, who lives in Tempe, Arizona, has sold $2.4 billion in shares since the start of 2024 as their price more than doubled. His son sold off more than $340 million of his stock last year, but Carvana equity still makes up 94 percent of his wealth. Father and son are estimated to be worth about $25 billion and $13 billion, respectively, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Garcia II, who at one point had 90 percent of his wealth tied up in Carvana stock, says he had to sell to diversify his holdings. Carvana now makes up about two-thirds of his wealth, and he says he’s satisfied with that. “Things can change,” he says, “but at this point I’ve done what I consider to be enough diversification.”

Believing in Carvana requires a certain comfort level with the idea of a family business and all the baggage that comes with it. And right now investors are happy to carry the bags.

At the company’s headquarters in Tempe, Garcia III is emboldened. He’s wearing a plain white T-shirt and blue shorts, as if he just walked off a pickleball court. He’s an intense, rapid-fire talker. “We will never make decisions that are aimed at satisfying skeptics. You can run in circles your whole life trying to satisfy skeptics,” he says. “Investors are smart, and they’ll figure that out, and they’ll agree with us or they won’t. And if they do, they can buy the stock, and if they don’t, they don’t have to.”

One thing he’s learned from Carvana’s comeback is that the company can no longer coast on hype like before and needs to establish a sustainable way for the business to grow. “We’ve learned the risks that you can face when you layer financial and operating risk together,” Garcia III says. “We’ve learned how to operate better.”

To that end, Carvana has reported a net profit seven quarters in a row. It made $944 million in the first nine months of 2025, the most recent data available, and more than 90 percent of it came from selling loans. “We’re expanding our loan platform,” says Chief Financial Officer Mark Jenkins. “I think we’re still in the relatively early days of expansion.”

Although Carvana isn’t building as many car vending machines these days, it’s increasingly willing to spend to get people’s attention. It signed NBA Hall of Famer and ubiquitous brand ambassador Shaquille O’Neal as a pitchman in September. O’Neal says he first learned about Carvana in 2016 when he drove past one of its glass-tower vending machines in Nashville, and he started doing research on the company when he got home. “I wanted that built at my house for my cars,” he says.

O’Neal’s voice and likeness are now on Carvana’s website, where visitors greeted with the slogan “Shaq-sized Selection” can chat with a Shaqbot artificial intelligence tool. Mad Men’s Jon Hamm also appears in the company’s commercials. Alexander Edwards, president of market research firm Strategic Vision, says the thing Carvana needs more than advertising is to improve customer experience. When you order a car through the site, it’s supposed to be dropped off at your house within a preselected three-hour window, but many customers complain about inconsistent or delayed deliveries, he says.

Adam Roderique, Carvana’s director of fulfillment strategy and analytics, says the company is investing in fixing that. Roderique is standing in the parking lot of Carvana’s 77-acre site in Tolleson, Arizona, outside Phoenix, where a crew behind him is busy loading and unloading used cars from trucks. There are 40 big rigs capable of hauling nine cars apiece to deliver orders as far away as Texas. But the company is trying to cut down on those long hauls. By opening locations all around the US and carefully managing where cars are stored to spread out inventory, delivering becomes cheaper for Carvana and quicker for the average customer, Roderique says.

Similar to how Carvana’s reconditioning facilities are sitting half unused, the company has enough trucks to move twice as many cars as it sells now. “There’s just so many links in our chain in terms of getting a car to a customer that we’ve had to build,” says Dan Gill, chief product officer. “Ten years ago, all of those technology solutions were quite immature, and there was a lot of spit and duct tape. When we went through our roller coaster in 2022, 2023, it gave us an opportunity to focus not on hypergrowth but get back focused on the unit economics of the business.”

That will be tough to do if actual economics turn against the business. In a downturn, people are more cautious about making big purchases, and fewer investors want to buy potentially hazardous assets like subprime auto loans. That would leave Carvana with lots and vending machines packed with cars that are harder to sell.

But for now business is booming. When a customer sells a car on Carvana, they either get it picked up by one of those trucks or drop it off at a vending machine. If they live in Arizona, there’s a good chance it’ll end up here in Tolleson. Inside the body shop, the smell of car paint hangs in the air, a cacophony of large fans hum away, car horns blare at random, and workers tinker under hoods. On this particular day, there are 5,500 cars on-site in various stages of reconditioning. Many dealers farm this sort of work out, but Carvana says it slashes costs by doing it in-house.

Workers on the floor with iPads track the progress of vehicles under repair using Carli, a production management system Carvana developed with Oracle Corp. The software can proactively order parts based on the condition of a vehicle and the model. (Some models are more likely to need certain repairs.) Carvana says Carli and other improvements have helped cut operations costs by $1,700 over three years. The company spends an average of $900 a vehicle compared with rival CarMax Inc., which spends about $1,200, according to JPMorgan analyst Rajat Gupta.

Back at headquarters, Garcia III is practically gloating. Whereas more than half of Carvana’s outstanding shares were shorted at the beginning of 2023, now it’s less than 15 percent. He bristles when asked about Carvana’s dependence on selling loans to support its bottom line and at the suggestion that the company should offer investors more financial data about it. The debt business is integral to the rest of Carvana, he says.

Sticking to his original vision is how Carvana will become, according to Garcia, the Amazon.com of cars. To do that, he says he needs to maintain the current management structure. That includes family control and his core team of executives, all of whom have been with the company for at least seven years. He doesn’t want a big board that second-guesses his decisions.

“My favorite thing to do is to try to be as close to a startup as we can be,” he says. “Smaller teams, smaller groups talking about it. More ownership by the individual.” Ultimately, though, that individual is Garcia.

By David Welch with Dylan Sloan and Tom Maloney