Delinquency rates on subprime auto loans are at records

One of the cylinders in the U.S. economic engine is causing some sputtering.

Since the pandemic, buyers on auto-dealer lots have encountered surging sticker prices and smaller incentives from automakers to lessen the blow. To afford an automobile, more consumers, especially lower-income families, have resorted to buying used cars and taking out longer loans.

Now, more are falling behind on their loans, signaling that lower-income consumers are struggling to afford payments as wages stagnate and unemployment ticks higher. While the economy has remained strong, and Wall Street has kept buying subprime auto loans, the auto market is evidence that not all is well under the hood.

The percentage of new-car buyers with credit scores below 650 was nearly 14% in September, roughly one in seven people, J.D. Power said last month. That is the highest for the comparable period since 2016.

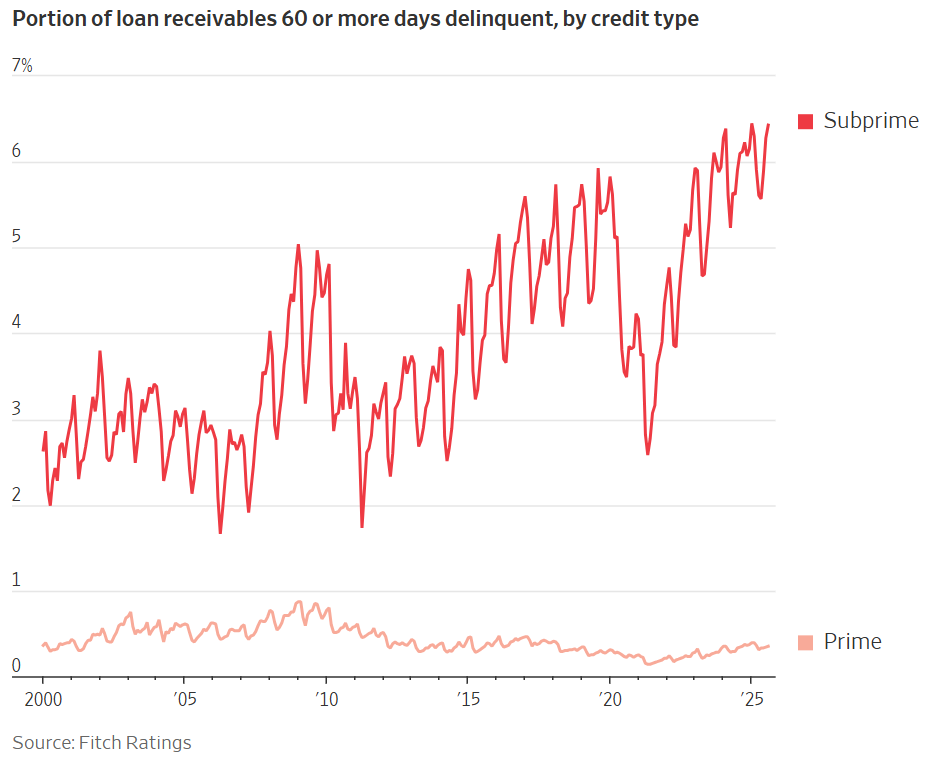

And the portion of subprime auto loans that are 60 days or more overdue on their payments hit a record of more than 6% this year, according to Fitch Ratings, while delinquency rates for other borrowers have remained relatively steady.

An estimated 1.73 million vehicles were repossessed last year, the highest total since 2009, according to data from Cox Automotive, an industry-research firm.

Delinquencies have leveled off but have remained higher than in the prepandemic period, economists say.

“These are borrowers who may have stretched their budgets to afford a higher price of the asset, as well as a higher payment because of the interest rate,” said Joelle Scally, an economic policy adviser at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

The stress placed on some subprime borrowers was highlighted last month with the bankruptcy filing of lender Tricolor Holdings, home to some 100,000 outstanding loans. The company, which catered to customers with little or no credit history or no Social Security number, faces allegations of fraud in its dealings with banks. (The company’s trustee has sought to hire an adviser to examine the allegations.)

Some industry analysts have said the Tricolor bankruptcy underscores the pressures on undocumented immigrants and other consumers with limited access to credit. Analysts at S&P Global Ratings recently warned investors about a number of securities backed by auto loans to consumers with little or no credit history, citing aggressive immigration enforcement.

So far, investors and analysts say Tricolor appears to be a unique event that is less likely a sign of impending broader concerns.

Subprime loans generally make up a relatively small portion of the auto-loan portfolios at banks, captive finance organizations and credit unions. But the finance arms of car companies loosened up credit over the summer, according to data from Cox Automotive, showing a willingness to take on additional risk.

Elevated new-car prices have been weighing on the industry for years, with average monthly payments rising to more than $750. Nearly 20% of loans and leases now exceed $1,000 in monthly payments.

Auto executives routinely cite a need to make more affordable cars, in part because some consumers have ended up shopping for used vehicles instead. Yet automakers often favor pricey trucks and luxury sport-utility vehicles because they produce fatter profits.

Ford last month said it would target low-credit buyers with lower interest rates to unload unsold F-150 pickups, its top-selling model. A Ford spokesman said that only 3% to 4% of the company’s portfolio of loans are backed by what it defines as higher-risk customers.

At General Motors’ GM 0.85%increase; green up pointing triangle credit arm, about 12% of its loans so far this year went to customers with FICO scores below 620.

“The customer is constrained and under pressure,” said Michael Lavin, president and chief operating officer of Consumer Portfolio Services, at a conference last month. Consumer Portfolio Services, a subprime auto-financing company, pulled back on lending this year, Lavin said.

The amount of Consumer Portfolio Services’ outstanding loans that ended up in repossession more than doubled since 2022, to nearly $98 million, in the second quarter of this year.

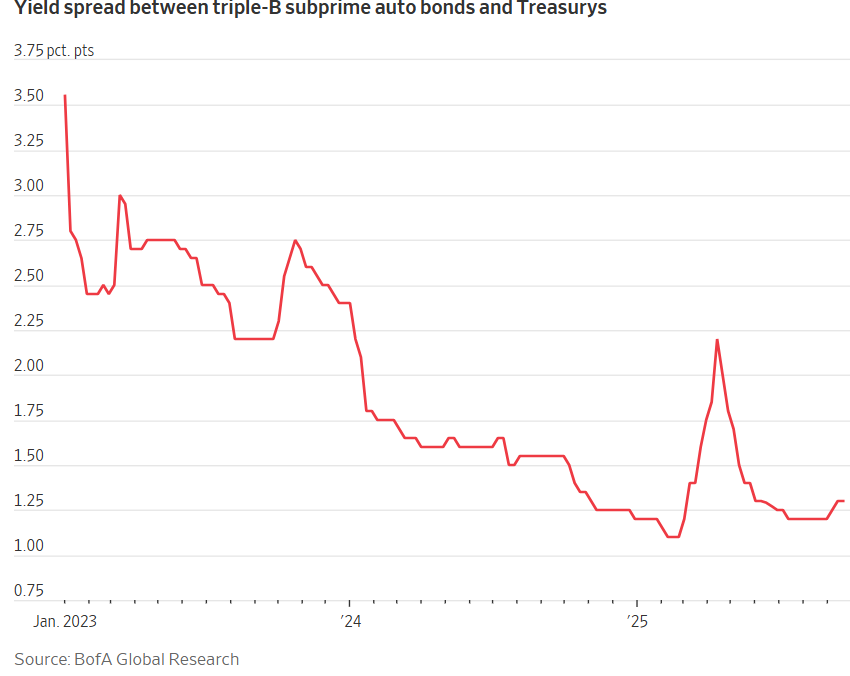

The rising delinquency rates aren’t spooking Wall Street much, as seen in the relatively low yields investors are demanding to buy bonds backed by subprime auto loans.

Investors are willing to buy those bonds despite elevated delinquencies in part because underwriting standards have tightened over the past couple of years and they expect less stress going forward, said Theresa O’Neill, an asset-backed securities strategist at Bank of America.