By Phoebe Sedgman, Jinshan Hong and Linda Lew

China’s dominance of the transition to electric vehicles is the latest source of geopolitical tension with the US and Europe, where policymakers face a costly catchup effort to avoid long-term dependency.

The European Union earlier this month heightened tensions with an investigation into Chinese subsidies for electric cars it says are flooding the market. The move brought the EU closer in line with the US, which has long had China in its sights.

Industry data and estimates by BloombergNEF show just how difficult building self-sufficiency or, more realistically, becoming just a little less reliant on China, is likely to be.

Asia’s largest economy has a deep stranglehold on battery production, leaving global carmakers dependent at one point or another on Chinese partners. The country’s battery makers supply some 80 percent of cells worldwide, backed by a mining and processing chain that increasingly resides in the country’s hands.

“Is it feasible to completely cut off the Chinese supply chains? Certainly not at the moment,” said Ilaria Mazzocco, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

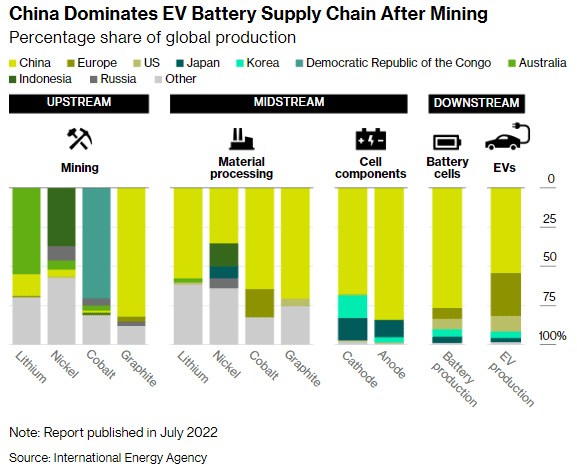

With the exception of graphite, mining is the area that’s least controlled by China, though the nation’s investment in African lithium mines to Indonesian nickel producers still gives it heft. But major US automakers like General Motors Co. have joined the rush to invest in the sector, and countries can utilize free-trade agreements to meet some sourcing requirements for EV components.

The next step — refining — is tougher to crack and China has spent years building its expertise. The country processes more than half the world’s lithium, two-thirds of its cobalt, more than 70 percent of its graphite and about one-third of its nickel, according to the International Energy Agency.

The process is typically highly polluting and creates toxic waste. Growing scrutiny around the environmental cost of digging up raw materials and making EVs complicates approval processes along this step of the supply chain.

But where China truly flexes its might is in cell components — the four key parts that are essential for a battery to work.

It has about 70 percent of the world’s production capacity of cathodes (the part of the cell that receives electrons) and more than 80 percent pof anodes (the part that releases electrons on discharge), and well over half of electrolyte and separator output. Those parts come together to make a lithium-ion battery, more than three quarters of which are made in China and mostly by just two firms — Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd. and BYD Co.

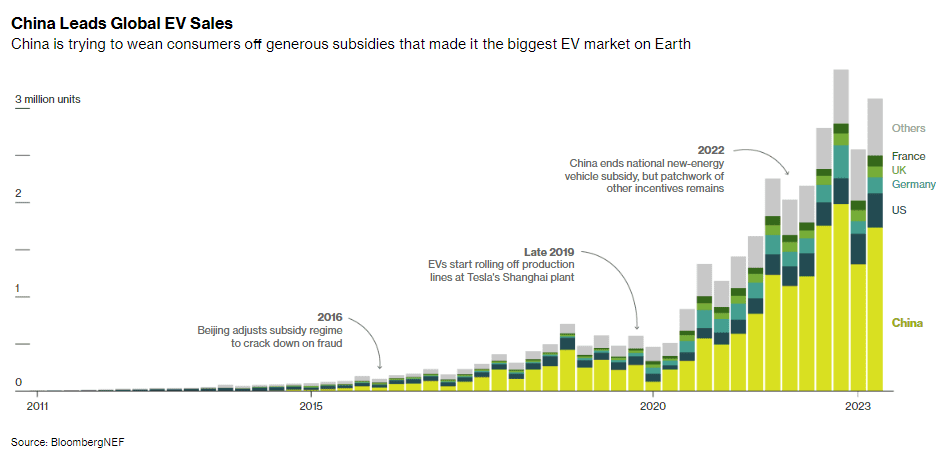

That extensive manufacturing infrastructure, coupled with generous subsidies and other support that costs the government billions of dollars each year, has made China home to the biggest EV market on Earth. In several cities, electric car sales are now approaching one in three.

t’s also meant Western countries are stuck playing catch up. And in the case of the EU, the bloc needs to meet some of the world’s most ambitious climate goals while navigating the complex bureaucratic web of 27 different nations.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has said China floods the EV market because it can sell cars at “artificially low” prices. There again, it’s all about the battery — the costliest part of an EV and where China best leverages its economies of scale.

China’s battery packs come in at $127 per kilowatt hour on a volume-weighted average basis while prices in North America and Europe are 24 percent and 33 percent higher, according to BNEF.

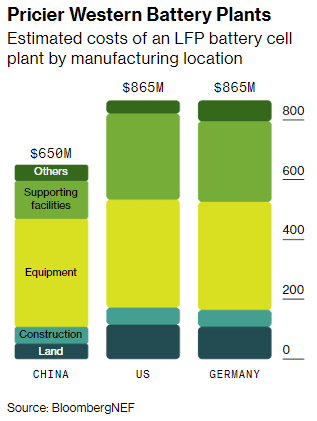

That makes battery-cell factories the most capital-intensive part of the push to diversify supply chains and, while difficult to pin down the exact spending needed to break away from China, snapshots show how quickly those costs will pile up.

Just a single lithium-iron-phosphate battery factory would cost about $865 million to build in both the US and Germany, Europe’s biggest car market, according to BNEF calculations. That compares with $650 million in China, in large part due to the country’s lower construction and labor costs.

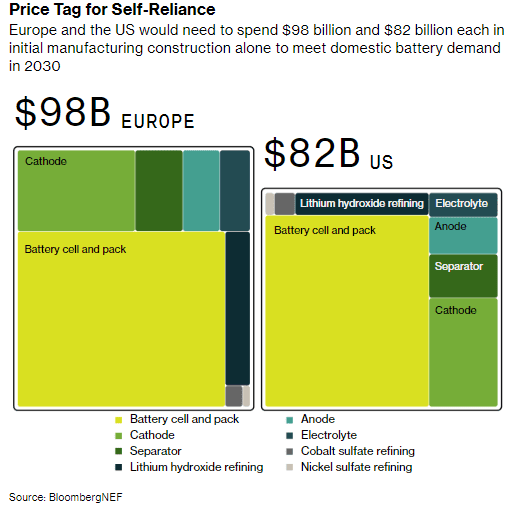

Taking a slightly broader view, BNEF data suggest that Europe and US would need to spend $98 billion and $82 billion, respectively, on the battery-metal refining to cell-making facilities they’d need by 2030. Battery cells and packs account for most of that cost, with mining raw materials and building and fitting out the factories to make the EVs themselves adding to the bill.

The EU estimates it will need another €382 billion spent across the entire value chain to be self sufficient by 2030.

It’s not just the hefty price tag. Adding to Europe’s difficulties is the potential far-reaching fallout from its China probe.

Should the bloc impose tariffs on imports from the country, Beijing is widely expected to strike back with retaliatory measures that could target anything from luxury goods to rare earths — a group of 17 elements that are critical for EV motors and which have emerged as a flash point in the China-US trade war. There’s also the risk the EU hits non-Chinese carmakers like BMW AG, which imports the iX3 to Europe from China.

A Chinese EV entering Europe is currently subjected to a 10 percent tariff. An additional duty of around 10 percent would be palatable, with a figure close to 25 percent indicating a breakdown in negotiations, said Zhao Yongsheng, a professor at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing.

“China-EU relations are not like that between China and the US, which are competitive and punitive,” he said. “We can achieve a tariff of around 10 percent if negotiations can stay on technical and rational terms rather than political factors.”

But with the world ushering in a new era of protectionism that’s upending global trade, the longer-term trajectory of battery and EV industries is likely to be more nuanced than a relentless pursuit of complete self sufficiency.

For a start, the West’s drive to shift away from China coincides with China’s own efforts to further exert its dominance.

Its EV sector is at the forefront of technology innovations and manufacturers are already unveiling a new generation of batteries that rely on sodium instead of lithium. In the short term, an economic slowdown is putting domestic EV demand on shaky ground, and that’s seen Chinese carmakers increasingly look overseas for sales.

Ultimately, the EU probe may even strengthen Chinese investment in the region to more easily navigate sourcing requirements or head off future geopolitical troubles. Chinese firms ramped up a push into South Korea’s battery sector to take advantage of the latter’s free-trade agreement with the US and boost the likelihood they’ll qualify for IRA tax breaks.

“There is no way the EU can do anything about Chinese carmakers coming into Europe now,” says }” data-terminal-type=”FUNCTION” data-terminal-value=”{BIO 6511846

That includes some of the industry’s biggest names. CATL is ramping up production at its battery-cell plant in Hungary. China’s SVolt Energy Technology Co. is set to expand its footprint in Europe to as many as five factories and is already in talks to supply the region’s carmakers with batteries.

The EU’s pledge to ban the sale of all new petrol and diesel cars from 2035 is also adding to pressure, and European Parliament elections set for mid-2024 will keep China’s EV dominance in focus, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. That means leaders need to be cautious about balancing political point scoring with pushing ahead with climate change mitigation efforts at a time when they’re urgently needed.

“At the end of the day, new energy industry development requires coordination through different links and different countries,” said