Being more mindful of the rate at which cars are coming off the road presents opportunities both for policymakers and industry participants.

By Andrew Grant

Around the same time each year, I find myself contemplating retirement.

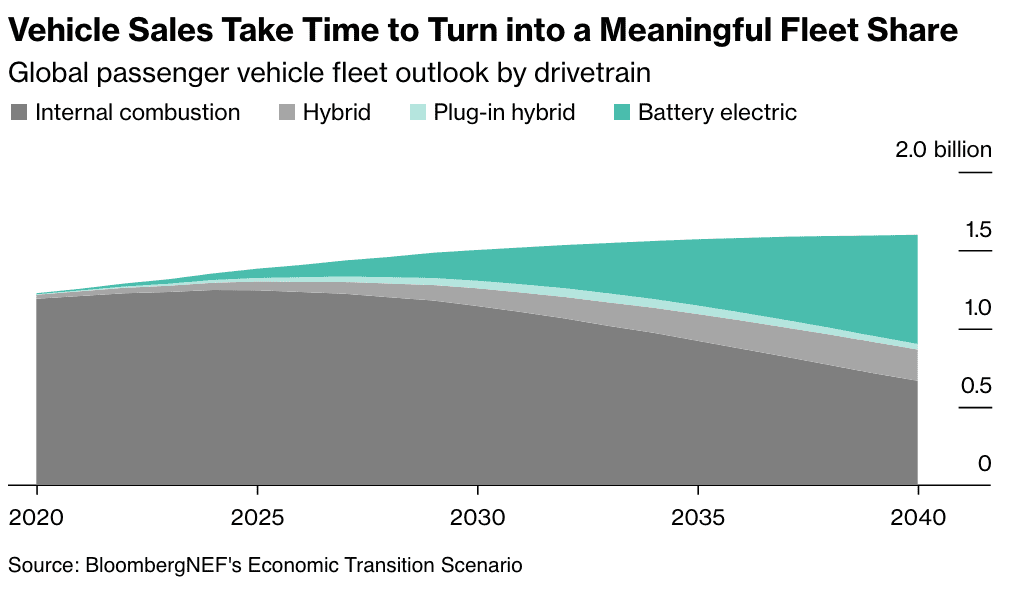

I don’t mean palm trees, sandy beaches and taking up new hobbies. Rather, I’m working on BloombergNEF’s annual outlook for light-duty vehicles, and mulling over the pace at which vehicles reach the end of their useful life and get taken off the road. The relationship between new sales and the rate at which vehicles retire ultimately determines how the vehicle fleet changes over time.

Across the automotive industry, there’s a tendency to focus on sales. After all, many of the companies in the sector generate revenue when ownership of vehicles or components changes hands. However, the total vehicles on the road — referred to either as the fleet, or the parc — is an important metric for where the world is on the journey to a zero emissions-capable fleet, and a variety of other industry-defining trends.

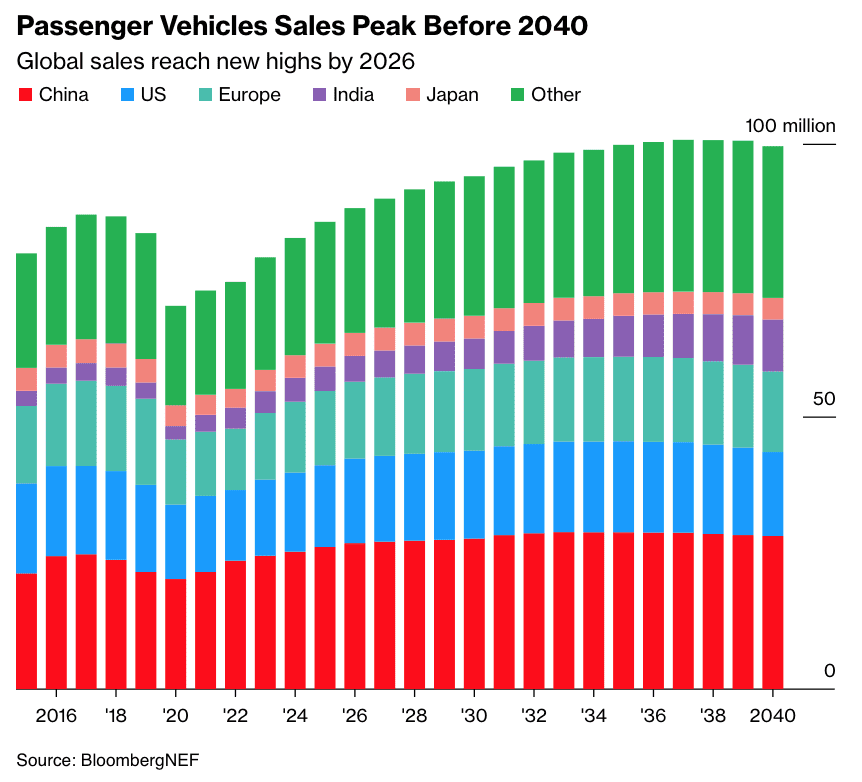

BNEF’s outlook sees global annual sales returning to 2019 levels in 2025 and to 2017 levels in 2026, with sales surpassing 100 million briefly in the late 2030s. Total passenger vehicle sales hit their highest point in 2037 in this edition of the outlook, one year later than our modeling indicated in the previous iteration of the report.

Around 3 percent of the global passenger-vehicle fleet leaves the road in a typical year. But with a global pandemic, semiconductor shortages, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and inflation sweeping the globe, the last few years have been anything but typical.

Consumers have responded by holding onto their vehicles for longer, leading to a growing fleet even as sales have lagged pre-pandemic levels. In our modeling, plug-in hybrid and battery-electric vehicles reach 75 percent of global passenger-vehicle sales by 2040. At this same point, less than half the fleet is comprised of these electric drivetrains.

Turning over the fleet quicker is possible, but would require policies focused on scrapping emission-intensive vehicles, rather than — or in addition to — the upfront purchase incentives for new cars that have been popular in the early stages of the shift to electric vehicles.

With the vehicle fleet continuing to rise steadily in the face of tumultuous sales and complaints about the profitability of EVs littering the earnings calls of incumbent automakers, look for the industry to lean more toward subscription-based offerings.

Subscription-based services can range from digital-only features — voice recognition and infotainment, for example — to the ability to access physical features in the vehicle, such as heated seats and even air conditioning. Thanks to built-in and aftermarket vehicle connectivity devices, the target market for these subscription offerings effectively is the entire active fleet of vehicles an automaker has sold.

General Motors already booked around $2 billion in subscription-related earnings in 2022 and wants to grow this to $25 billion annually by 2030. Rivals Ford and Stellantis expect in-vehicle subscriptions to grow into businesses worth approximately $20 billion to each automaker by 2030.

Whether you’re measuring emissions from the tailpipe or the earning potential of automakers, paying attention to what vehicles are actually in use is crucial. As major auto markets pass the inflection point on the sales of electric vehicles, it could be more important to focus on what vehicles are leaving roads, rather than what vehicles are leaving showrooms.