The money dealers charged over makers’ suggested prices factored into a nearly 16 percent rise in the consumer-price index in recent years

By Ben Eisen

Markups on new cars were a key force behind the current bout of inflation, according to new research published this month.

Those extra dealer profits contributed between 0.3 and 0.7 percentage point of the nearly 16 percent rise in the consumer-price index between the end of 2019 and the end of 2022, a study published in a U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics journal found.

Auto demand surged after customers got pandemic stimulus checks, while supply-chain snarls reduced supply. The sales prices for new cars skyrocketed. Much of that additional money went into the pockets of dealers, according to the research.

“It was really from famine to feast for dealers,” said Michael Havlin, the economist who wrote the paper. He formerly worked at the BLS but wrote the paper, which was reviewed by the bureau’s subject-matter experts, in a personal capacity.

Car-price increases were a factor in the inflation that has roiled the economy over the past couple of years. New-vehicle inflation contributed nearly 1 percentage point to the rise in inflation over those three years. The Federal Reserve has been aggressively lifting interest rates to cool down the economy, hoping to tame prices.

The role of corporate profits in driving inflation is a heated subject. A recent study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City argues that markups across industries accounted for more than half of inflation in 2021, with firms raising prices in anticipation of costs increasing later.

Economists said Mr. Havlin’s study lines up with the data they are seeing. “It’s a narrower look at a sector where the magnitude is much larger than the rest of the economy,” said Andrew Glover, who co-wrote the Kansas City Fed paper, on Friday.

Still, many contend that inflation is driven by market forces that include many players, so it can’t be pinned on one group, especially when demand for products far outweighs supply.

It is “absurd” to argue that dealers contributed substantially, or even at all, to inflation, a spokesman for the National Automobile Dealers Association said. “By that logic, every consumer who sold or traded in a used vehicle for more than its Kelley Blue Book value profiteered off that sale and thus bears responsibility for contributing to consumer inflation,” he said.

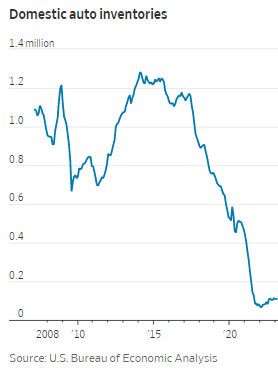

For much of the prior decade, dealership margins were under pressure. Customers became more cost-conscious after the 2008 financial crisis, making it difficult for dealerships to fully pass along the fast-rising prices set by manufacturers, Mr. Havlin found in his prior research. Dealers also had lots of inventory. They made less from car sales and instead earned more from the sale of financing and insurance products.

But during the height of the pandemic, the supply-demand imbalance for new vehicles meant dealerships could suddenly charge more for each one. In aggregate, dealers had new-vehicle margins of 11.5 percent in 2022 versus 4.9 percent in 2019, according to the research.

Rising new-car prices upended the entire auto market. Used-car prices also surged as customers turned to cheaper options. Borrowers took out bigger auto loans to afford their cars, more of which are now going delinquent. Older cars stayed on the road longer.

“What we saw with the supply-chain crisis is that dealerships were able to reassert their position as an inventory management system,” Mr. Havlin said. “And dealers are the ones with inventory.”

Heather Bernikoff and David Raboy said their local dealership told them last spring that a Ford F-150 Lightning electric truck they had ordered for their cattle ranch in Catheys Valley, Calif., would be marked up $10,000 more than the roughly $45,000 sticker price.

Michael Lopretta, general manager at Razzari Auto Centers, where they had reserved the car, said pricing was based on the short supply and high demand for the vehicle.

The couple called about a half-dozen dealerships until they found one 2½ hours away that didn’t have markups. They took home the truck late last year.

“Not everybody has the time or inclination to scour around multiple dealers to find somebody who is going to want to do that,” Mr. Raboy said. “Most people are going to go to their local dealerships.”

A Ford Motor Co. spokesman said most Ford dealers are charging around the sticker price.

Ms. Bernikoff and Mr. Raboy recently joined advocacy efforts to pass a bill in the California legislature that would prohibit dealerships from marking up electric vehicles.

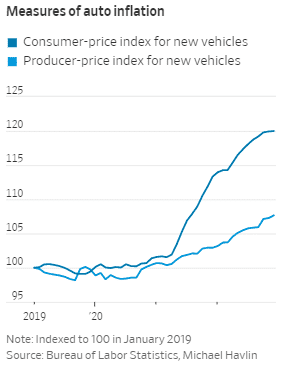

Mr. Havlin studied markups by analyzing the differences between how new-car prices are measured in official government data. The consumer-price index, which tracks what customers pay for cars, and the producer-price index, which tracks what manufacturers charge dealers for cars, increasingly diverged over the past few years.

Mr. Havlin’s work showed that dealer markups were largely responsible for the gap between the two indexes. A new index he created to estimate dealer markups on new cars, which was informed by a separate measure of PPI for dealers markups, showed a rapid rise in 2021 that peaked at 17.7 percent in September 2022.

Mr. Havlin cross-checked the analysis against the financial disclosures of some of the large publicly traded auto dealerships. AutoNation Inc. marked up vehicles by almost 15% in the fourth quarter of 2021, versus less than 5 percent two years earlier, according to his calculations. Lithia Motors Inc. marked up cars by almost 16 percent in late 2021, up from about 6 percent two years earlier.

Inflation for financing, insurance, extended warranties and other products also increased during this period. Such products aren’t constrained by supply, but Mr. Havlin concluded that the demand allowed dealerships to tease even more profit from that part of the business.

“Those innovations didn’t go away,” he said.