Leasing this year hits lowest point since 2009; auto makers are limiting incentives

By Nora Eckert

Fewer Americans are leasing new vehicles because of higher prices and scarcity on dealer lots, a pullback that could crimp the supply of used vehicles and interested buyers in the coming years.

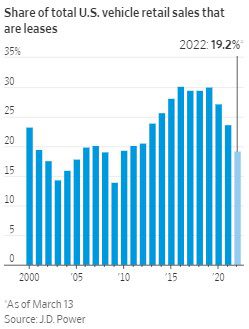

The percentage of new cars and trucks leased during the Covid-19 pandemic has declined, dropping to 19 percent of overall retail sales so far this year through March 13—the lowest since 2009, according to research firm J.D. Power. Leasing accounted for about 30 percent of the broader retail market in the years leading up to the health crisis, the firm’s data shows.

The car shortage has prompted many auto makers to drop the discounts and other types of promotions they typically offer to make leasing attractive to car shoppers.

“Buyers face sticker shock when they come out of one lease into another,” said Mike Maroone, chief executive of Maroone USA, which owns six dealerships in Colorado and Florida.

In some cases, leasing a luxury model now costs about the same in monthly payments as financing one, spurring more consumers to buy out their existing leases or put their next vehicle lease on pause.

For instance, a 2022 Volvo XC90 is leasing for an average of about $951 a month, $8 more a month than to finance the vehicle, according to data from car-buying site Edmunds. In 2019, it was about $216 cheaper to lease than to finance the same model.

The drop-off in leasing is yet another way the U.S. car market’s recovery from the early days of the pandemic is being hampered by a mismatch in supply and demand.

The higher lease rates are also adding to concerns about affordability, as leasing has long been a popular option for consumers looking to get into a new vehicle but at a lower monthly payment than if they were to buy the car outright.

Leasing is typically offered by an auto maker’s financing arm, the entity that owns the vehicle and essentially rents it to the customer for a fixed period—often two to three years. At the end of the term, the customer can either buy out the lease at a preset price or return it to the dealership. If returned, the car company usually resells the vehicle at auction.

Leasing has been particularly important for the luxury-car market, where for brands like BMW, Mercedes-Benz and Volvo it has historically accounted for nearly half of their sales, according to J.D. Power data.

While leasing is still generally cheaper, the monthly payments are rising at a faster clip than those on financed vehicles. In February, the average monthly lease payment was $560, about 19 percent higher than it was in the same month two years ago, according to Edmunds. The average monthly cost of financing a car was $637 in the same month, a 12 percent increase over February 2020, the car-shopping website’s data shows.

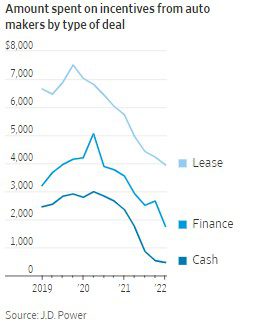

To make a lease more attractive, car companies often contribute money to the deal. In the first quarter of 2020, auto makers spent on average $7,000 per vehicle to discount leases, compared with around $4,200 per vehicle on financing, according to J.D. Power.

But such spending can also cut into profits. Lately, with inventories tight, car companies have had less incentive to offer such promotions, executives and analysts say. The average industry spending on leasing has dropped 44 percent in the past two years, to around $4,000 per vehicle in early 2022.

Scott Keogh, CEO of Volkswagen Group of America, said he doesn’t see a rebound soon for leasing to its previous levels, because car companies are trying to put priority on more lucrative sales.

“But don’t get me wrong, we’re not walking away from it,” Mr. Keogh said. “I think it’s still a smart thing.”

For now, consumers such as 36-year-old Los Angeles resident Schuyler Hunt are looking for workarounds to the higher leasing costs.

Mr. Hunt, who works in advertising, was about to turn in his leased Audi A3, planning to replace it with a hybrid or electric car. He said he knew he would likely have to pay more, but was stunned to find most dealers quoting him double his current lease payment of $360 a month.

“I laughed, and I think I said something inappropriate,” Mr. Hunt said, referring to one lease offer with a payment of more than $700 a month. Instead, he said he bought out his lease on the Audi because he determined it would be cheaper to finance the car than enter into a new lease.

The impact of such decisions is likely to have longer-term implications for both auto makers and dealers, who rely on leasing to both drive repeat business and help replenish preowned inventories. Already, the drop-off in leasing is taking its toll on the number of vehicles coming back to dealerships.

In the fourth quarter of 2021, GM Financial—the financing arm of General Motors Co. —reported its U.S. lease returns had dropped to 1 percent, down from 62 percent during the same period a year ago.

Auto executives and dealers say many customers are holding on to their leases longer or buying them out at the end of their terms, in part because they can’t find a replacement on the lot.

“Leases do create this wonderful steady stream of customers who have to come back to market,” said Thomas King, an analyst for J.D. Power.

Vehicles coming off lease help ensure the used-car market has a consistent supply of low-mileage models that are only a few years old. With fewer people leasing, the pipeline is also being disrupted, compounding an existing shortage of used cars on dealership lots, dealers say.

Rising interest rates could help reverse the current dynamic, making borrowing more expensive and pushing more customers to consider leasing, said Mark Templin, chief executive of Toyota Financial Services USA.

“If you went back in history and look, leasing ebbs and flows based on interest rates,” Mr. Templin said. “When interest rates come down, people will finance more. When interest rates go up, leasing will go up.”

Write to Nora Eckert at nora.eckert@wsj.com