By Jinjoo Lee and Telis Demos

Prices of new and used vehicles are at record highs, bolstered by a semiconductor supply crunch that has kept a lid on car production just as consumers are itching to get out and shop for them. Used cars and trucks were 45.2% more expensive in June than they were a year earlier, while new cars were 5.3% pricier, according to the Labor Department. Monthly payments don’t look all that different to consumers, though, thanks to lower rates, longer terms, or putting up more cash. For new cars, average monthly loan payments increased just $7 in the first quarter of 2021 compared with a year earlier, according to consumer-credit reporting company Experian. Monthly loan payments for used cars rose $19, or 5%, in the same period.

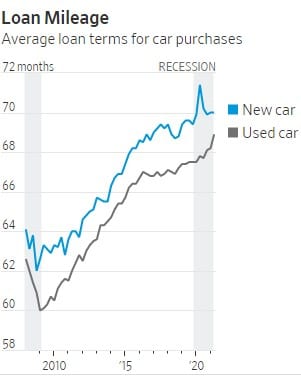

Loan durations had been getting longer even before the pandemic. The average length of an auto loan was 70 months for new cars and 68.9 months for used cars in the second quarter, according to data from Edmunds; 10 years ago, they averaged 64 months and 62 months, respectively. Much of that happened as competition grew among lenders and as car prices gradually increased, with auto makers adding new technology and customization options on vehicles. Longer payment terms were designed to make vehicles look more affordable.

There is reason—both for consumers and lenders—to be wary of longer-term loans. For consumers, one obvious catch is that you generally wind up paying more interest over the life of the loan. Another is that you could end up owing more than what the car is worth. The latter concern is especially pertinent today because sky-high car prices will eventually come back down to earth when the supply crunch for new cars eases. That means if a consumer tries to sell the car or if it is totaled in an accident, the money from a buyer or insurance company might not cover the loan balance.

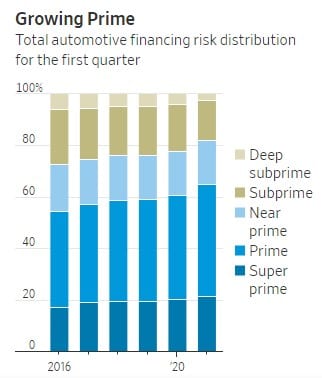

A 2018 analysis from Moody’s Investors Service showed that the cumulative losses of longer-term prime auto loans (those 72 months or longer) originated between 2003 and 2015 were two to five times higher than shorter-term loans originated during the same period. That is partly because longer duration loans tend to go to less creditworthy borrowers, according to Moody’s. Credit profiles of car buyers do look better today and consumers have more saved up thanks to stimulus payments and spending less during pandemic lockdowns. The average credit score for both new and used car buyers has increased since 2016, according to Experian. The share of prime lending has also increased over that period, while subprime lending is near record lows.

The flush bank accounts of car buyers is helping some of them make deals involving more cash. Loan-to-value ratios for car loans have “come in better as people are putting in more cash on the deals,” Santander Consumer USA Holdings’ chief financial officer, Fahmi Karam, said on the lender’s earnings call in April.

High used-car prices have also meant that lenders could command higher prices for the repossessed cars when loans default. Auto defaults were at a 10-year low as of May 2021, according to the S&P/Experian Auto Default Index. Recovery rates for auto asset-backed securities reached all-time highs in April, with prime recoveries rising above 100%, according to S&P Global Ratings. Declining car prices will likely have the opposite effect.

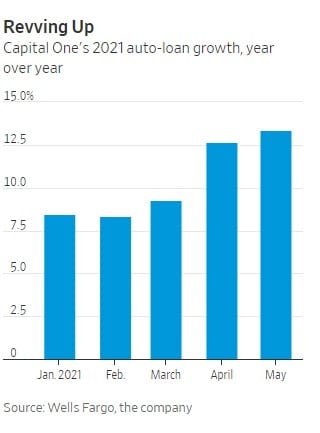

How severe that reversal will be is an open question, and one that lenders will have to ask themselves as competition grows hotter among them, possibly leading to even longer terms and lower rates. Donald Fandetti, an analyst at Wells Fargo, says competition is picking up for auto loans as banks struggle to find good ways to put huge deposit inflows to work.

There are reasons to believe that the eventual market-value decline of cars, new and used, might not be so steep. Jessica Caldwell, an industry analyst at Edmunds, says the SUVs and trucks recently favored by consumers tend to lose less value than passenger cars over time. This is especially true for pickup trucks, which tend to be used for practical purposes and are always in high demand. The eventual introduction of new vehicle inventory will likely be a “trickle and not a flood,” which should also reduce downward pressure on car prices, she added.

And while vehicles do depreciate, technology advances have meant that they have a longer useful life. The average age of cars and light trucks in operation in the U.S. rose to 12.1 years this year, according to IHS Markit, from 9.6 years in 2002.

A sudden reversal on car prices’ direction could cause shock to consumers and lenders. But plentiful stimulus, fatter wallets and cars’ longer useful lives should act as air bags for any accidents along the way.

Write to Jinjoo Lee at jinjoo.lee@wsj.com and Telis Demos at telis.demos@wsj.com