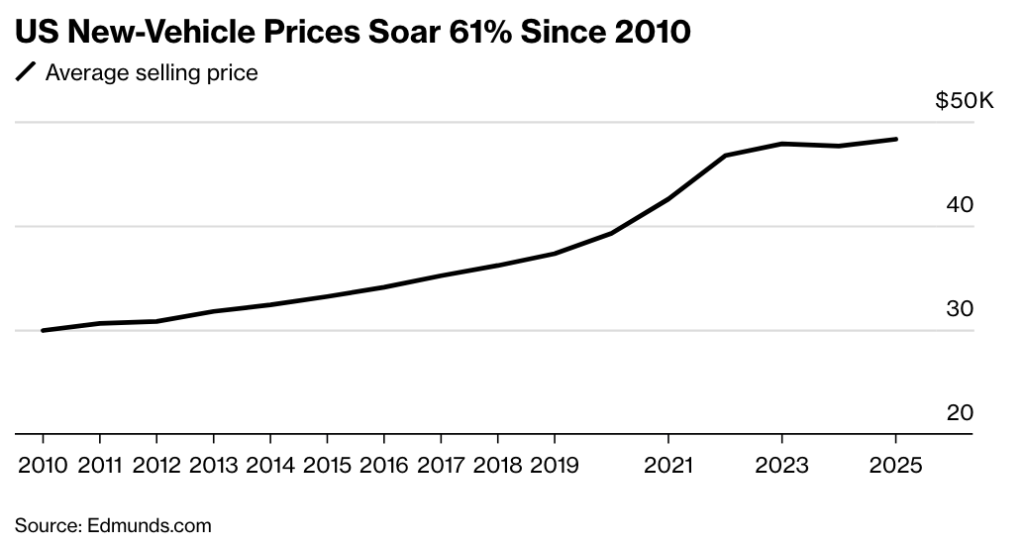

With affordability top of mind for US voters as November’s midterm elections approach, Republicans have been focusing attention on one of the most visible pain points for consumers: the price of a new car. The average figure broke $50,000 for the first time last September and hit $50,326 in December, according to the Kelley Blue Book car buying guide. Researcher Edmunds.com calculates that the average has risen 61 percent since 2010.

While incomes have grown over that period, too, they haven’t kept up. It took 36.2 weeks of average household income in the US to buy a new car at the end of 2025, a figure down from a pandemic peak but a few weeks longer than the pre-Covid norm. As a result, more Americans have been pushed out of the new-car market or forced to take on more debt to stay in it. President Donald Trump and his allies in Congress have cast fuel-economy rules and other regulations as the culprit behind consumers’ pain. Democrats blame tariffs the president has imposed on imported cars and auto parts.

In reality, the reasons for the escalation in new-car prices are more diverse than either side’s accounting of them. And there are still other factors inflating the costs of car ownership beyond the sticker price.

An EV bump

The breaking of the $50,000 threshold in September was partially the result of an uptick in sales of electric vehicles, which have an average selling price some $8,000 higher than that for all cars. EV sales hit a record in the US in the third quarter of 2025 as consumers rushed to take advantage of a $7,500 federal tax credit for such purchases before it expired on Sept. 31. EVs accounted for 10.6 percent of new-vehicle sales in that period, compared with 8.6 percent in the same period a year earlier, according to Cox Automotive. Without the tax incentive, the share plummeted to 5.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2025.

Tariff effects

So as not to jolt buyers with sticker shock, automakers have taken steps to absorb the cost of tariffs without overt price hikes. But some are spreading small price increases across their lineups in an effort to avoid making individual, impacted models uncompetitive.

Pandemic effects

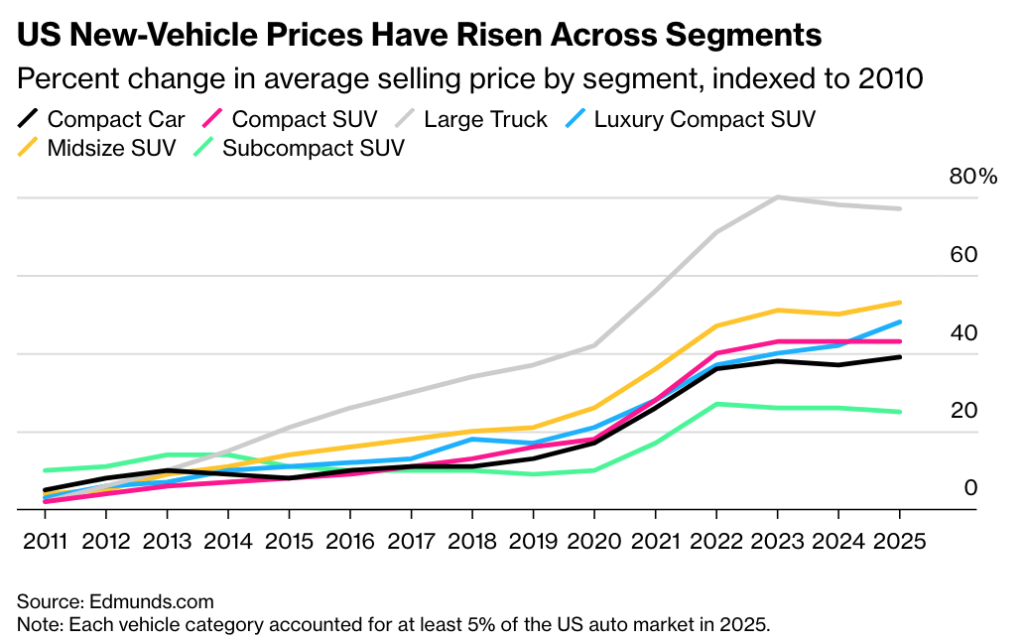

For more than two decades before 2020, American consumers were able to buy increasingly better, safer and more powerful yet efficient cars without feeling a dramatic change in price. Mark Wakefield, global auto market lead for consultant AlixPartners, attributes that largely to globalization and the formation of supply chains that constantly shifted to countries with the lowest cost of labor, a trend the US is now trying to reverse.

The pandemic strangled those supply chains, driving up the cost of raw materials such as steel and aluminum and causing chip shortages that shrank the number of vehicles carmakers were able to produce. As labor and material costs rose and demand began to outstrip supply, automakers began to subsist on smaller inventories with higher prices, rather than churning out as many vehicles as possible to gain market share. “They’ve been crazily profitable through this period because they’ve been able to not compete on volume and instead they’re taking it in price,” Wakefield says.

Automakers have begun again to offer deals and discounts to support demand. But, overall, such incentives are still lower than they were before the pandemic, according to Cox Automotive. That’s in part because manufacturers are wrestling with the added costs of tariffs.

Bigger, feature-loaded vehicles

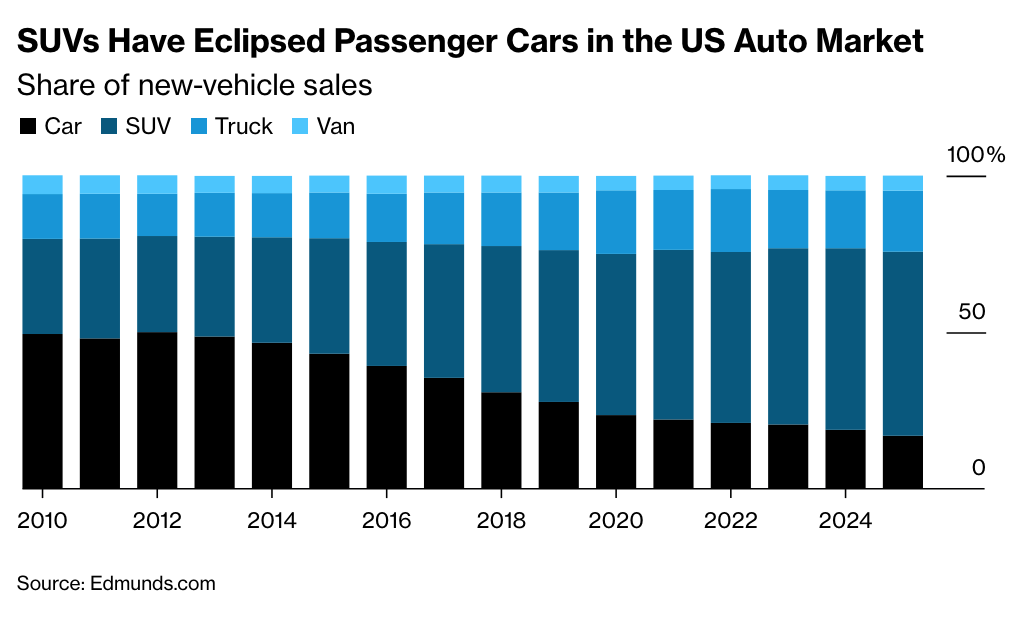

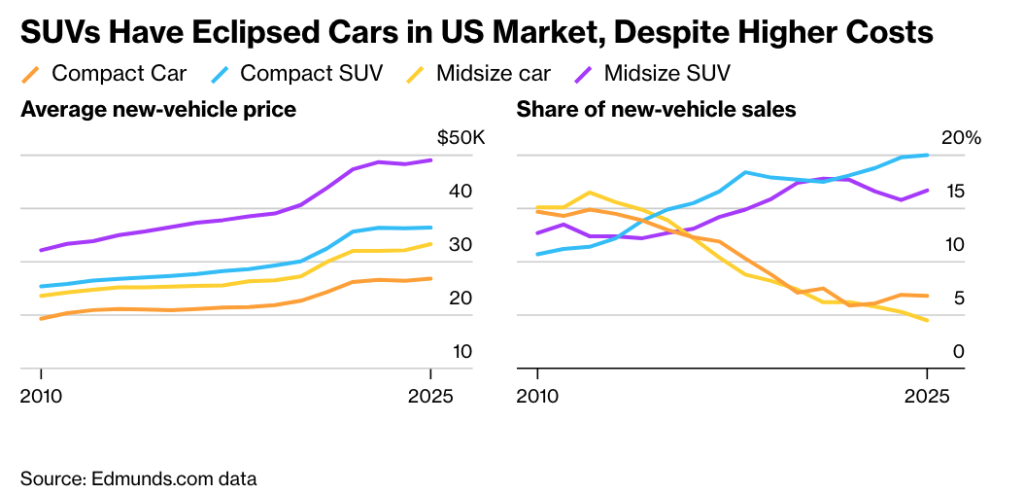

But the upward drift in car prices predates the pandemic, Trump’s tariffs, and the jump in sales of pricey EVs. It’s been happening over decades and can be traced in large part to Americans’ love of large vehicles. “If we were looking at the recipe for how we got here, it is going to be one of the first ingredients on that list,” said Ivan Drury, director of insights at automotive researcher Edmunds.com.

The American passion for big cars is part of a broader cultural affinity for big — big houses, big TVs, big steaks. Automakers leaned into it by outfitting increasingly larger sport-utility vehicles and pickup trucks with features previously found only on cars and engineering the vehicles to drive like smooth-riding sedans, rather than rugged haulers. “The engineering has gotten so good that all the negatives of the past with SUVs and pickup trucks — poor ride quality, overweight, no features — are gone,” said Drury. “Now you can hop into virtually any vehicle of any size and it will drive as well as a sedan.”

Automakers also marketed the big rigs as being far safer than the low-slung sedans that previously served as the main mode of transportation for American families. “We’ve been marketed to death,” Drury said, with messages such as “you better keep your family safe, you need all-wheel drive.”

Helping to seal the deal, automakers markedly improved fuel efficiency on SUVs and pickups, thanks in no small part to stringent fuel economy regulations. They’ve even begun to offer gas-saving hybrid propulsion systems on the biggest vehicles. One-in-five Ford F-150 pickups now is a gas-electric hybrid. “Twenty years ago, the image was of the gas guzzling SUV,” Drury said. “The improvements that have been made allow you to have things that were once forbidden fruit.”

But all those improvements come at a high cost. As US automakers stopped selling sedans — killing high-volume compacts such as the Ford Focus and Chevrolet Cruze — in favor of higher-margin SUVs and pickups, they were left with some of the highest prices on the market. The average price of a vehicle made by the biggest American carmakers — General Motors Co., Ford Motor Co. or Stellantis NV — is now $54,380, 13 percent above the industry average, according to Edmunds.

Improvements, some driven by regulation

Car costs have also been inflated by technological improvements, many of which have been driven by safety standards and emissions regulations. Rear-view cameras are now standard in all new cars after US regulators mandated the technology starting in 2018. Automakers are also using more advanced metals to both improve safety and reduce vehicle weight, the latter helping vehicles comply with fuel economy requirements.

A Republican campaign to significantly relax fuel economy rules and eliminate what the head of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has characterized as “vestigial regulations” — outdated requirements that no longer advance safety goals — could make it easier for the auto industry to make more affordable cars, says Erin Keating, executive analyst with the research firm Cox Automotive.

At the same time, consumers have “very willingly embraced” regulation-driven enhancements in cars, says Eric Noble, president of The CarLab, an automotive product and design consulting firm outside Los Angeles. “If someone slams into you at a red light, would you like to have their front bumper stop at your front seat back, or at your trunk?”

Some safety features that aren’t required by regulation, such as lane-keep assistance and blind spot detection, have also been welcomed by many drivers. And cars have become more lavish. Big infotainment screens and heated steering wheels come standard in more models, while features such as massage seats and high-end stereo systems are premium options.

Other factors in overall costs

For the large majority of new-car buyers in the US who finance their purchase, interest adds to overall ownership costs. As the Federal Reserve raised its benchmark interest rate to tame inflation, average rates on 60-month auto loans doubled to 8 percent in 2024 compared with the figure in 2022, before ticking down to about 7 percent at the start of this year.

“Financing costs have more than doubled as a share of household income,” says Keating. As a result, she says, the mix of people buying new cars is skewing more toward the affluent, while those making less than $75,000 have left the market.

On top of financing costs, new technology has made cars more expensive to repair and insure. The average cost of auto insurance premiums rose nearly 65 percent in the past five years, while repair costs climbed 44 percent, fueled by a shortage of technicians, according to data compiled by Cox.