Lingering questions about battery EVs signal that having a backup technology isn’t as crazy as it might sound

The old debate about whether electric cars should be powered by batteries, Tesla-style, or with hydrogen fuel cells, such as the Toyota Mirai, appears to have been won hands-down by batteries in recent years. So why are companies still investing in hydrogen cars?

The facetious answer is that they may be designed to convey political messages more than actual passengers. The serious one is that there are still plenty of doubts about battery EVs as a universal solution for decarbonizing road transport.

British petrochemical giant Ineos Group is the latest company to reveal a fuel cell EV. The automotive division of Jim Ratcliffe’s privately-owned group on Thursday presented an adapted version of its Grenadier off-roader, itself a new take on the old Land Rover Defender, at the Goodwood Festival of Speed in the English countryside.

The hydrogen-powered Grenadier is just a proof of concept: Ineos is years away from committing to mass-producing a fuel cell EV. Still, why is a startup such as Ineos Automotive, which was founded in 2017, bothering with hydrogen at all when sales of EVs driven by batteries are so much stronger?

Ineos hopes to launch a battery EV in 2026 that it envisages being used in urban and everyday settings. But it also wants a low-carbon way to deliver the same kind of extreme off-road capability and long range its customers might expect from its gas-guzzling Grenadier. This is where hydrogen excels.

“I don’t think one technology is superior to the other. I think they’ve got different uses. And I think we need a mix of technologies in the future,” says Lynn Calder, chief executive officer of Ineos Automotive.

This is a variant of what has become a consensus view: That fuel cell EVs, which are more energy-dense, are needed for long-distance trucking, buses and the odd niche light-vehicle application, while battery EVs, which are more energy-efficient, are the better solution for decarbonizing your typical family car.

Even companies that have spent decades working on fuel cell cars stress the technology’s heavier-duty applications these days. At a technology briefing last month, Toyota said it had 100,000 potential fuel-cell orders from third parties, most of them for commercial vehicles. Honda and Hyundai, the other champions of hydrogen cars historically, talk of selling their systems to manufacturers of trains, ships and construction machinery, among others.

But behind the consensus linger questions, too, about battery technology—notably how fast it can realistically take over the family-car market. One well-documented worry focuses on limited supplies of battery metals such as lithium, and another concerns the impact of battery EV charging on the power grid. Hydrogen EVs, with their completely different supply chain, could ease these scalability problems, which have a sharp geopolitical edge given China’s dominance of battery supplies.

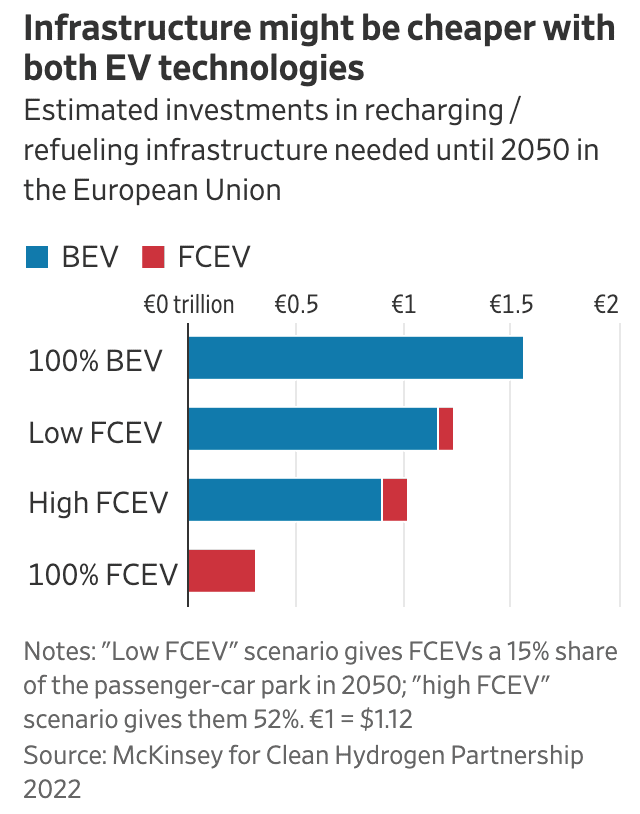

BMW is currently touring the world with a fleet of hydrogen-adapted iX5 sport-utility vehicles to make the case for the technology, despite having little if any involvement in commercial vehicles. One of its arguments is that building roadside infrastructure for both battery EVs and hydrogen ones will end up being less expensive for countries than just building an EV infrastructure, which will require huge upgrades to the power grid.

BMW’s fuel cell iX5s are a political calling card: It is easier to galvanize the attention of policy makers if you can show them a car. The same might be said even of the Japanese and Korean fuel-cell EVs you can actually buy: Companies need them to show commitment and raise interest among politicians who often find it easier to focus single-mindedly on battery EVs.

Politics matter because hydrogen has for years been caught in a chicken-and-egg conundrum where investments in vehicles only made sense if there was refueling infrastructure, and vice versa. Now more infrastructure is planned, particularly in the European Union and China, which is one reason companies along the vehicle supply chain are increasing their investments. Automotive parts giant Bosch this week said it would spend an additional $1.1 billion on hydrogen projects, starting with a fuel-cell stack it is supplying to U.S. trucking startup Nikola.

A virtuous cycle might finally be under way in heavy trucks. In time, this could in turn bring down the cost of fuel cells and hydrogen to the point that the technology becomes competitive with battery EVs in the car market, too—though this is still an outside bet given the potential of battery innovations.

Above all, the surprising persistence of the hydrogen-car dream speaks to the uncertainties and complexities of the transition to lower-carbon rides. The curious alliance between Tesla and China has put battery EVs far in the lead for now. But tinkering away in the garage at a backup technology, particularly one that can be sold into other markets, isn’t a crazy thing for carmakers to do.

In an era of rapid technological change, neither manufacturers nor investors can be too confident about seeing around the many corners ahead.