A scarcity of EV battery materials pushes car companies and miners to work closer together; for both, there is a learning curve

By Mike Colias and Scott Patterson

When General Motors GM -0.09%decrease; red down pointing triangle began outlining plans in 2020 to fully switch to electric vehicles, it didn’t account for one critical factor: Many of the battery minerals needed to fulfill its plans were still in the ground.

“I remember seeing a report from our raw-materials team at the time saying, ‘There is plenty of lithium out there. There is plenty of nickel’,” said Sham Kunjur, an industrial engineer now in charge of securing the raw materials for GM’s batteries. “We will buy them from the open market.”

GM executives soon came to discover how off the mark those projections were, and now Mr. Kunjur’s 40-person team is scouring the globe for these minerals.

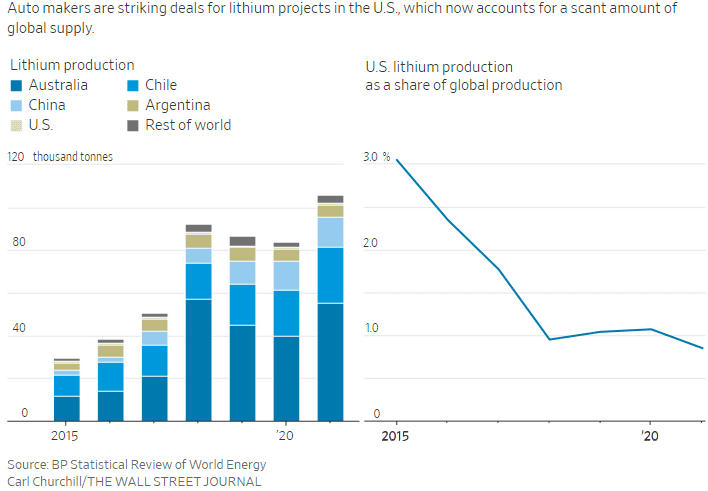

The auto industry’s shift to EVs has triggered a scramble to lock in supplies of lithium, nickel, graphite and other materials core to battery making, much of which are currently mined and processed outside the U.S. in places such as China and Australia.

The specter of an eventual EV battery shortage is pushing car companies to get more directly involved in the mining business, one that is largely foreign to them and introduces new risks.

The effort reflects a belated realization by auto executives that the mining sector—despite the promise of huge demand—hasn’t mobilized to unearth enough of these battery minerals.

Now, car companies are playing the role of both investors and customers. Many are using their deep pockets to help get mines up and running, while guaranteeing to purchase the extracted materials.

The result is a haphazard alliance of two sectors that in many ways make strange bedfellows.

The car business is ruled by rigid factory schedules and the clockwork precision of its vast, global supply chain. In mining, cost-overruns and delays are commonplace, and even the most sophisticated operators don’t always know if these risky ventures will pan out.

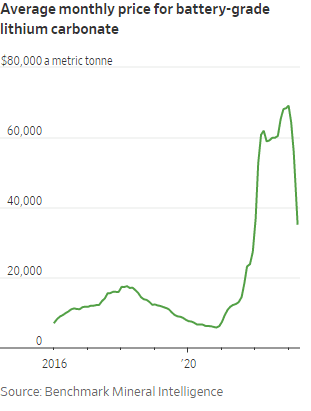

Automakers say they want stable, hedged prices; miners are accustomed to wild market swings.

“You’ve got the mining people with dirt under their fingernails and some great stories at the bar about exploring the Amazon,” said Todd Malan, head of climate strategy at Talon Metals TLO 0.00%increase; green up pointing triangle, which is developing a nickel, copper and cobalt mine in central Minnesota.

And the car people? “You can spot the autos guys because they usually have the tech-bro vests on,” he added.

For automakers, the pressure is on to solve this supply problem.

New battery plants are popping up across the U.S., and car companies are pouring billions of dollars into electric-vehicle factories. They are moving swiftly to stay ahead of regulations restricting tailpipe emissions and don’t want to be left behind as EV sales take off.

One of the biggest bottlenecks is lithium, a soft white metal that is the workhorse of rechargeable batteries. Processed-lithium demand is expected to far outstrip supply in coming decade unless the mining industry dramatically expands production, analysts and producers say.

“Desperation is a strong word,” Paul Graves, chief executive of lithium producer Livent, said in November. “But certainly [there is] a lot more concern among the auto manufacturers today about whether they will have enough.”

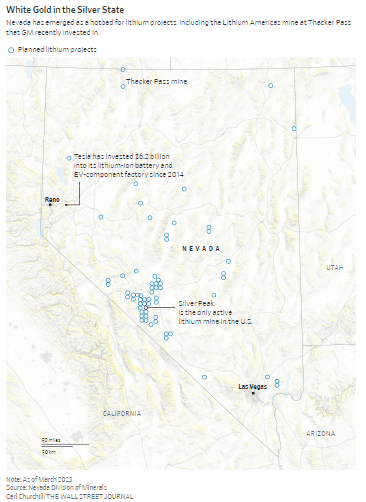

In January, GM agreed to invest in a joint-development project with Vancouver-based mining firm Lithium Americas LAC 1.49%increase; green up pointing triangle. The deal gives GM exclusive rights to lithium extracted from a remote-desert site in Nevada called Thacker Pass, which the companies say is one of the largest known lithium sources in the U.S.

Ford Motor F -0.26%decrease; red down pointing triangle in March said it would invest an undisclosed amount to buy an equity stake in an Indonesian nickel mine. Netherlands-based Stellantis STLA -0.62%decrease; red down pointing triangle said in February it would invest $155 million in a copper mine in Argentina.

“You have to secure your supply. If not, you’re out of business,” Stellantis CEO Carlos Tavares said in April.

EV pioneer Tesla TSLA -0.97%decrease; red down pointing triangle has worked for years to improve its access to battery supplies, after facing shortages early on.

In 2022, Tesla contracted directly with mining companies or refiners for more than 95% of the lithium hydroxide and 55% of the cobalt it needed for batteries, the company said in a recent report. It is unclear if those figures refer only to Tesla’s in-house batteries or also to ones it received from suppliers. Tesla didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Even so, CEO Elon Musk has said the lack of a steady pipeline for processed lithium is a major obstacle. “Lithium is almost everywhere on Earth, but pace of extraction/refinement is slow,” he tweeted last year.

The minerals deficit traces its roots to early last decade, when a commodity super cycle fueled by voracious Chinese demand went bust, wrecking the debt-laden balance sheets of mining producers. These operators had issued billions of dollars in debt to fund huge mining projects.

Rather than invest in new projects, the world’s mining giants distributed billions of dollars in dividends to shareholders.

As automakers increased their electric-car investments in recent years, executives began to discover that battery- and raw-materials supply chains don’t work like those for steering columns or spark plugs.

In late 2017, Volkswagen VOW -1.26%decrease; red down pointing triangle summoned several cobalt producers to its global headquarters in Germany to discuss securing cobalt supplies, said Tony Southgate, head of cobalt marketing for mine operator Eurasian Resources Group.

During discussions, VW asked what his firm charged for cobalt. Mr. Southgate said he quoted the current market price, roughly $30 a pound at the time.

“What about the VW discount?” the VW officials asked, according to Mr. Southgate. He replied there wasn’t one. “They couldn’t get their head around that,” he said.

Volkswagen declined to comment.

As the industry’s rush to electric cars accelerated in 2020, predictions of a dire battery shortage were growing louder, and prices of critical minerals were climbing.

Car executives began to realize the mining firms didn’t only need buyers—they needed partners to help shoulder upfront investments, say executives involved in the conversations.

“The miners have something that is very, very important for the car companies,” said John Startin, a senior managing director at Evercore, focused on global metals, materials and mining.

But he added: “They don’t have a lot of alternate sources to get the capital.”

The carmakers, which typically rely on their suppliers to source raw materials, initially were hesitant about fronting the cash for inherently risky mining operations. Often, such projects are vulnerable to delays, bureaucratic hurdles and price volatility. Unforeseen technical hurdles can also cause costs to spiral.

The miners, too, had reservations.

“I’m not sure they believed the EV transition was happening to the extent that it is,” said Tanya Skilton, who joined GM from mining giant Rio Tinto in 2017, and is now a director on Mr. Kunjur’s team.

Mr. Kunjur, who a few years ago was buying truck-engine parts and alloy wheels in GM’s vast purchasing department, discovered the urgency of his mandate last year during one of his first meetings with GM Chief Executive Mary Barra. The topic: How GM would secure all the battery materials needed to hit its target of selling two million EVs annually by 2025.

“I thought you had figured this out yesterday,” Ms. Barra told his team, Mr. Kunjur recalled.

Around that time, he began vetting Lithium Americas, and scheduled a meeting with its CEO, Jonathan Evans, at a mining conference in Phoenix. As talks progressed, Mr. Evans explained the company was looking for two or three separate customers to buy 10,000 or 15,000 tons of lithium each, which would cost an estimated $2.3 billion to develop.

“We said, ‘We want all of it,’” Mr. Kunjur recalled.