Supply constraints make a return to 2008-style discounting hard to imagine. The question is what will happen when those constraints end.

Don’t worry too much about a recession hitting Detroit. The real concern should be normalizing supply.

The U.S. new-car market is stuck in a low but lucrative gear as manufacturers struggle with production. General Motors warned Friday that its second-quarter profit would be lower than previously expected due to parts shortages curtailing deliveries to dealers. First-half sales across the market came in at about 6.8 million, according to Wards Intelligence, down 17 percent from the same period last year.

Market share is being driven by vehicle availability more than desirability. Toyota outsold GM in the U.S. for the first time last year, and again in the first quarter, because the Japanese company initially handled procurement challenges better. But it too has succumbed lately; GM regained its old spot atop the sales charts in the most three months.

Yet supply constraints have created surprisingly profitable conditions for dealers and manufacturers. With few new vehicles on lots, the average price of a new one hit a fresh record of $45,800 in June, according to an early reading by J.D. Power. The losers have been consumers and parts suppliers, which are typically locked into long-term contracts.

Without many signs that the environment is changing, the question is why Detroit auto-maker stocks, which were very strong in 2021, had such a terrible first half. GM and Ford both fell 46 percent —much worse than the broad market.

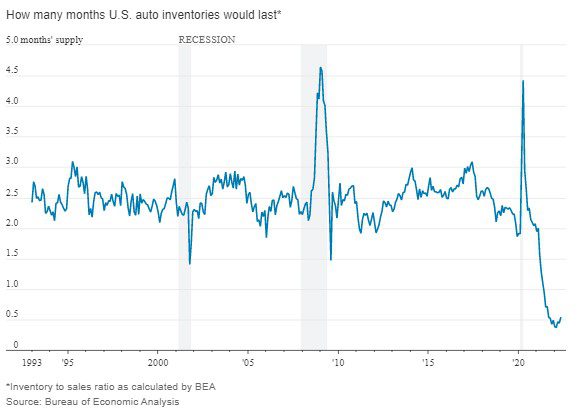

The obvious answer is rising recession risks as interest rates rise. The average new-car loan cost 5.08 percent in May, up from 4.45 percent a year earlier. In the 2008 downturn, manufacturers had excess inventory and discounted aggressively to keep cash flowing to support their high fixed costs.

But a recession might not make so much difference in the current new-vehicle market which, in addition to being supply-driven, is now the preserve of the affluent. Buyers with incomes of less than $50,000 now account for less than a quarter of sales, down from roughly 40 percent at the start of 2016, according to Cox data.

Another concern is high pump prices, which ought to make the gas guzzlers Detroit specializes in less attractive. There are some signs of shifting tastes in the used-car market: Prices of small cars have been stronger than those of pickup trucks lately, says Charlie Chesbrough, senior economist at Cox. With inventories much lower for new vehicles, though, the trend might not feed across soon.

This isn’t to say that Detroit had a great second quarter. Rising raw-material prices are starting to squeeze auto makers more as supply contracts get renegotiated. The cooling used-vehicle market won’t give their financial-services arms the tailwind they got last year. Profits are surely past their best.

Still, the real test of car makers’ mettle will come when supply once again exceeds demand. Manufacturers say they won’t fall back into the old trap of overproducing, but this is hard to believe when the industry still has significant excess capacity and investment in electric-vehicle production will lead to even more.

However this plays out, normalization could take years. As supply gradually recovers, risks from a slowing economy need to be set against the benefit of pent-up demand. Consulting firm AlixPartners doesn’t expect U.S. new-vehicle inventories to start rising meaningfully from their current multidecade lows until 2025. That could mean the next few years are more comfortable for car makers than recession-obsessed investors seem to think.

Cars don’t offer value at the moment, but car stocks just might.